September 1975

September 1975

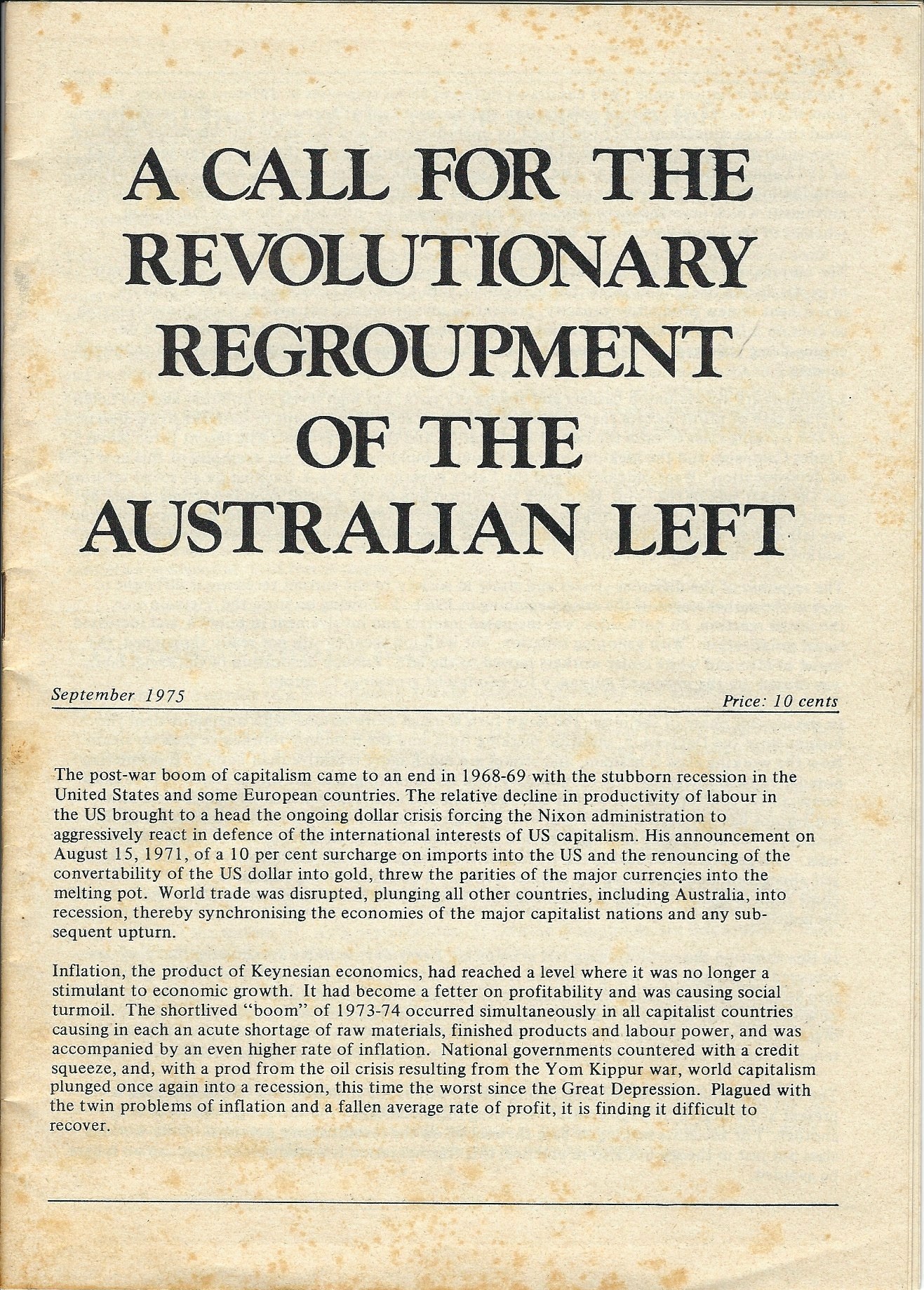

A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment

of the Australian Left

Introduction (2017) by Robert Dorning and Ken Mansell

Momentous changes occurred in Western societies in the 1960s and 70s. A wave of youth radicalisation swept many Western countries. Australia was part of this widespread generational change. The issues were largely common, but varied in importance from country to country. In Australia, the Vietnam War and conscription were major issues. This radicalisation included the demand for major political change, and new political movements and far-left organisations came into being. A notable new development in Australia was the emergence of Trotskyist groupings. However, as the wider movement subsided with Australia's withdrawal from the Vietnam War, the Australian Left became fragmented and more divided than ever. It was in this environment that, in 1975, "A Call for the Revolutionary Regroupment of the Australian Left" was published by the "Melbourne Revolutionary Marxists" (MRM).

"The Call" includes a description of the evolution of the new Left movements in Australia including the Trotskyist current to which MRM belonged. MRM was a break-away from the Communist League, an Australian revolutionary socialist organisation adhering to the majority section of the Fourth International. At the Easter 1975 National Conference, virtually the entire Melbourne branch of the CL resigned en masse from the national organisation. The issue was the refusal of the national organisation to accept the application by Robert Dorning (a leading Melbourne member) for full membership on the grounds he held a "bureaucratic collectivist" position on the social nature of the Soviet Union, rather than the orthodox Trotskyist position of "deformed workers' state". The former CL members then formed a new group, MRM, which developed a strong commitment to regroupment of the Australian Left.

The Call was published under the name of MRM, however the principal authors were two MRM members, Robert Dorning, former editor of the socialist journal "Tocsin" and a lecturer in Marxist Economics at the Victorian Labor College, and Ken Mansell, anti-war activist and labour historian. The draft was presented to the group and after some editing was endorsed and printed by the group. The publication of The Call prompted regroupment discussions in Melbourne and Sydney.

A web version of The Call has been published on the Bob Gould website "OzLeft" with an introduction by Bob Gould. Gould's introduction is quite complimentary and generally accurate. However, he neglects to mention the organisation that published the booklet and incorrectly says it was "published anonymously". Nor is he correct saying the group was "basically two or three people". He is also confused about the authors. His reference to one as a trade union official is mistaken. Dorning was a trade union activist, but never a paid official. One necessary correction in his (presumed) reference to Ken Mansell's initial collection of oral history interviews ("with communists and socialists") is that they were deposited in the State Library of NSW, not the Australian National Library. Whoever was responsible for the OzLeft web version of The Call took the liberty of making many stylistic and grammatical alterations to the text of the original document. The version presented here is identical to the original document.

We, Robert Dorning and Ken Mansell, believe the document was significant at the time, and that it is still relevant.

A CALL FOR THE REVOLUTIONARY REGROUPMENT OF THE AUSTRALIAN LEFT

The post-war boom of capitalism came to an end in 1968-69 with the stubborn recession in the United States and some European countries. The relative decline in productivity of labour in the US brought to a head the ongoing dollar crisis forcing the Nixon administration to aggressively react in defence of the international interests of US capitalism. His announcement on August 15, 1971, of a 10 per cent surcharge on imports into the US and the renouncing of the convertability of the US dollar into gold, threw the parities of the major currencies into the melting pot. World trade was disrupted, plunging all other countries, including Australia, into recession, thereby synchronising the economies of the major capitalist nations and any subsequent upturn.

Inflation, the product of Keynesian economics, had reached a level where it was no longer a stimulant to economic growth. It had become a fetter on profitability and was causing social turmoil. The shortlived "boom" of 1973-74 occurred simultaneously in all capitalist countries causing in each an acute shortage of raw materials, finished products and labour power, and was accompanied by an even higher rate of inflation. National governments countered with a credit squeeze, and, with a prod from the oil crisis resulting from the Yom Kippur war[1], world capitalism plunged once again into a recession, this time the worst since the Great Depression. Plagued with the twin problems of inflation and a fallen average rate of profit, it is finding it difficult to recover.

The surge in inflation since 1970 has drawn different social responses in different countries, but generally it has caused political polarisation and increased social unrest. In Australia, workers made good the wage squeeze of 1972 (enforced by unemployment and the union bureaucracies' electoral support for the soon-to-be-elected ALP) by massive industrial activity throughout the second half of 1973 and the first half of 1974. The sudden onset of the current recession, and its serious nature, with the highest unemployment since the '30s, has brought a virtual halt to the widespread strike movement which nevertheless is incessantly being goaded by inflation. The wage indexation schemes of the Labor government[2] have caused further confusion and hesitancy.

The current recession is the most serious for capitalism since the war. The fall in the average rate of profit during the long post-war boom together with uncertain economic prospects inhibits investment in new productive capacity, preventing investment-led expansion. Governments trying to contain inflation by cutting spending can only deepen the slump. Unemployment, and declining living standards of wage-earners, means that consumer demand will not stimulate economic activity.

Capitalists are always union bashers and always cry poor, but high levels of inflation and the fallen average rate of profit dictate that capitalism must now seriously attempt to slash the living standard of the working class to raise the rate of exploitation and thereby profits. The recent futile Metal Trades Campaign and the lock-out in the Melbourne building industry are examples of this new level of determination. Wage indexation and the Labor government's back tracking on all social reforms are the other side of the coin. Held back by caution due to the present economic climate, and by a reluctant union leadership, strikers are suffering significant defeats; whilst the divided revolutionary left stands nonchalantly on the sidelines as if these defeats will not have lasting effects on workers' attitudes and combativity.

The response of the different classes and strata in society to the current recession is different to that in the earlier stages of the crisis beginning in 1969. Following on from the Vietnam war, the initial reaction, on both sides, was increased interest and involvement in politics, and increased social polarization. With galloping inflation, but with job security still not really threatened, the mood of blue and white collar workers moved to the left. Enough dislocation of the social fabric was caused by the increased militancy for neo-fascist groupings to sprout.

In the current phase of the crisis, the down-turn is much more serious, with unemployment the highest since the Depression, inflation marking time, and the economy refusing to pick up steam. Now the working class is hesitant, and strikes are much more tentative than before. It is entering popular consciousness that the economic system is foundering, and the initial response is to draw conservative conclusions and to pull back and wait and see. The belief in bourgeois ideas and institutions has not been undermined, even though people are worried by the seriousness of the situation. We are passing through a period where the mood of workers is one of wary watchfulness. This general mood makes the threats of the bourgeoisie that much easier to realize. When self abnegation does not bring the respite, but only a decline in living standards, workers will become restless again, this time strengthened knowing that restraint has no other effect than to hurt themselves.

In this situation the revolutionary left is helpless. Every day, workers are showing that they are prepared to struggle, but being divorced from them, the left can offer little assistance. Divided into sects, each with a handful of members, it can have little effect on the attitudes and activities of workers. What is needed is a full frontal attack on the rationale of capitalism, and an organization strong enough to make itself heard. As the crisis in capitalism deepens, the impotence of the left becomes more obvious, and the need for a revolutionary leadership more urgent.

The foremost objective factor obstructing the growth of the revolutionary left in Australia is the present acute degree of fragmentation isolating the members of the various groups from one another. For socialists seeking to base themselves on the revolutionary potential of the working class not just in theory but also in practice, this fragmentation is a predicament that can no longer be avoided.

a critical history of the recent australian left

Ten years have passed since the Vietnam war first jolted the inactivity and indifference of political life in the Western World over the previous two decades. When the Vietnamese stood up and defied the imperialist bombs that rained on them they invoked dreams of revolutionary optimism in representatives of a fresh generation untrammelled by moods of defeat.

Today, the new revolutionary left that was born in Australia lies fragmented in a plethora of sects. The following interpretative history is an attempt to explain the process that produced them in order that it may be possible to overcome this fragmentation. It is limited by space and therefore necessarily generalised.

It was a process of crises and splits that brought the new revolutionary left in Australia into being and provided the impetus for its development. Each fragmentation took the movement to a higher level. However, when the crystallization of sects became general on the left, fragmentation, which had previously been a stimulus to development, turned into a fetter. Today, the left rests exhausted on a plateau. Further fragmentation can only signify the impotence of the revolutionary left in its present form.

Fragmentation has also affected the left of other capitalist countries. But whereas in Europe and the United States, most of the revolutionary organizations have an ideology, a tradition and an organization which can be traced to the forties, or at least to the fifties, every left wing organization in Australia (with the exception of the Communist Party and its offshoots), having had no Australian predecessor, is of recent origin.

ELEVEN THESES ON DERIVATIVE SECTS

The absence in Australia of a revolutionary Marxist tradition placed the new generation of revolutionaries in a theoretical and practical vacuum. They lacked an organization present in Australia capable of satisfying their needs. Thus, the various ready made finished programmes held out overseas proved to be an irresistible temptation for those demanding an immediate solution.

* * *

There is nothing inherently wrong in adopting a political programme that has originated overseas. Capital and labour are both international, and a Marxist programme must necessarily be so. But each existing "international" maintains that it is the embodiment of internationalism, and, on this basis, is given devoted, unquestioning loyalty by its adherents in Australia.

* * *

The revolutionary left in most capitalist countries seems unable to respond to the historic needs of the proletariat in a period of deepening capitalist crisis. This, in part, reflects the inadequacy of the programmes of the various left wing organizations. If existing programmes are inadequate in their countries of origin, obviously they will be more so in countries of adoption.

* * *

In Europe, and in the United States, the theory and practice of the mentor organizations are a product of their own experience and development and can be modified as circumstances dictate. Each Australian sect, however, embraced its imported programme as an act of faith. This act froze each into a carbon copy of its original, unable to progress unless its parent does.

* * *

In each sect, the individuals who can most faithfully recite the imported doctrine assume the prestige of the international body and become the local leadership. A leadership which is the embodiment of the imported programme can only proclaim it, not question it. The reflected glory is used to overawe members. Those who do not submit can only be purged.

* * *

Each Australian revolutionary sect can only reproduce the theory developed by its mentors overseas. Moreover, each of the finished programmes is inadequate. Each sect is therefore unable to overcome the historically-based backwardness of theory and practice in Australia, and is unable to develop theory and practice for, and a knowledge of, the Australian terrain where it will be tested.

* * *

Each carbon copy sect must defend its imported ideas and practices externally as well as internally. Because its ideas are borrowed, each sect can only reiterate to other equally informed, but equally closed minds, well-known ideas which each knows have been fully debated in international forums without either side having admitted it was wrong. Sects based on unquestioning loyalty to imported programmes can only perpetuate their isolation from each other. None has the intellectual freedom to admit that areas of its own programme are wrong, and that areas of another are correct.

* * *

The imported programmes have required several decades to become "finished". Foisted onto the Australian left, they introduced the international internecine factional warfare into the Australian context, magnifying differences here which were often merely tactical (given the common backwardness and immaturity of the left) or the products of regionalism; they prevented common actions which may have brought revolutionaries together in spite of these superficial differences; they prevented a bona fide theoretical debate on the left which may also have contributed to revolutionary unity.

* * *

Because each "international" has anointed itself international proletarian vanguard on the strength of its "correct" programme, each derivative sect finds it legitimate to appoint itself the embryo of the revolutionary party in Australia.

* * *

Most of the sects accept the strategical necessity of regroupment. But each arrogantly demands, as a prerequisite, the acceptance of its own imported programme. At the international level, however, the differences between the creators of the finished programmes continue to magnify with the passing of time.

* * *

Revolutionaries, and their organizations, necessarily take time to mature. Even if the imported finished programme did express the needs of the proletariat, some time would be required in Australia before there were the necessary revolutionary skills to realize it. These skills will not be established by a diktat from afar.

The importers of the finished programme are not sufficiently theoretically developed to critically judge it, nor are they sufficiently practically experienced to judge it in application. Hence, though a sect may possess the most developed theoretical products of the human brain, overawing many with whom it comes into contact, its membership has not necessarily internalized the method which constructed the now gobbled-up formulae in the first place. The programme has an ideological character - its adherents are unable to concretely analyse concrete conditions.

The practice of the sect is the result of a diktat from afar. Theory is not a guide to practice, whilst its practice cannot correct or modify theory. Theory and practice both remain ossified and barren. Nonetheless, so compelling is the fantasy world of the importers of finished programmes that they believe that their practice, though fruitless, could not be otherwise.

THE REBIRTH OF THE LEFT

VIETNAM - THE SPARK

The Vietnam war plunged into the tranquil waters of Australian life when Menzies announced conscription in November, 1964. For the first time in twenty years, it became possible for many to cast off the blinkers of cold war mythology and develop a sustained critique of capitalism. So conservative and monolithic was the Communist Party, which exercized a near absolute hegemony over those opposed to capitalism, that it was from within an ALP milieu that the combustible material of the new revolutionary alternative first began to accumulate. The ALP adopted an anti-Vietnam war stance that was far to the left of the Communist Party and the long established peace movement. For the following two years, the new radicals organized in ALP-sponsored groups such as the Vietnam Day Committee (VDC) and the Youth Campaign Against Conscription (YCAC), and placed their bets on Labor.

Calwell's defeat on November 28, 1966, in the Vietnam election, was a decisive turning point for the new movement. It confirmed Whitlam and the Labor Right in their course, but it also steered most of the new youth activists to the left. The election had exposed parliamentarism as a useless vehicle for radical causes. The new movement began to grope for revolutionary alternatives to the time-honoured institutions of the bourgeoisie.

THE FIRST FRAGMENTATION - FROM REFORM TO REVOLUTION

The search for a revolutionary course in the absence of a Marxist tradition in Australia, and of a national revolutionary organization, led to the first of the many fragmentations that took the new revolutionary left forward. No longer united behind ALP slogans, the new movements in Melbourne and Sydney seized upon different ideologies proffered by international bodies, which inevitably obscured the common social base and goals of the two parallel movements and magnified what were at that time merely superficial differences. Before long the ideologies had become paramount and their practitioners held them in awe.

In Sydney, it was the imported ideas of international Trotskyist organizations, previously unknown except to a lonely handful, which won acceptance among most revolutionaries. In Melbourne, where Ted Hill's "Marxist-Leninists" had become a pole of attraction since splitting from the CPA three years earlier, it was the slogans of Mao's cultural revolution which took hold.

MELBOURNE - THE RISE AND FALL OF MAOISM

In Melbourne, the most revolutionary minded of the new activists had been most influenced by their actual experiences. Only those ideas that seemed to explain these experiences were adopted. Their ideology, therefore, was nothing more than a patchwork of simple Leninist truths.

Student protestors had borne the brunt of Johnson's security men in October 1966. The Little Red Book seemed to offer the best explanation of state power; and, at its height, the Chinese cultural revolution seemed to offer an attractive model of communism, especially for those students who had experienced it at first hand. Also, China had given strong verbal support for wars of national liberation, particularly Vietnam.

The new revolutionaries in Melbourne were constrained at demonstrations in 1967 by the old Peace Chiefs. They undertook spectacular initiatives on campus however. Their aid to the National Liberation Front broke through the bounds of legitimate dissent and inflamed Monash University, soon to witness the first Australian experiments in student power.

The French May of 1968 popularized the notion of students acting as a vanguard detonator of working class struggle. Even before they had established links with workers' organizations, radical students were acting in the name of a worker-student alliance. The adventure of the 1968 July 4 demonstration - the first really violent demonstration in Australia in recent years - seemed to confirm the belief, then widely-held among revolutionaries, that violent confrontations with the police would bring students and workers together, expose the real nature of the state, and start a prairie fire.

In February 1969, the broad alliance of campus revolutionaries established "The Bakery"[3] as a centre for the newly-formed Revolutionary Socialists (Rev Socs) organization. There, those with a penchant for activism soon became impatient with theorizing and turned a full circle into the bosom of the old left. In January 1970, they formed the Worker-Student Alliance (WSA) in sympathy with the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist), the local Maoist organization.

WSA reached its peak together with the anti-war and student movements. But, by the end of 1971 these movements had begun to decline. Then, in 1972, China delivered two shocks - the Nixon visit and Bangla Desh. As Chinese foreign policy moved openly to the right, WSA followed, and, despite some internal dissension, the red flag of the organization, which had become an embarrassment to a movement opting for collaboration with the patriotic bourgeoisie, was replaced by the Eureka flag.

Today, student Maoism is on the wane in Australia. The anti-Trotskyist violence of student Maoists at LaTrobe University is the final flurry of an empire in retreat. Student Maoism in Australia has become an anachronism: it belonged with the peace marches and the conservative limbo of the mid-sixties, from which it liberated so many - this much at least we owe to Albert Langer, the Plekhanov of the Australian revolution.

The student Maoists had created from nothing a political base upon which others could build. They had been unable to complete the process themselves. Their particular ideology reflected, albeit in a partial way, the objective position, hopes and aspirations, not of the working class but of a section of the student population.

The political moods of the student milieu tend to be ephemeral. This can be explained in part by the rapid turnover of the student population, but more generally by the position of students in society. Students are outside the exploitative process of production and are motivated primarily by their emotional and intellectual needs. Though they may react explosively to certain issues, and to the contradictions of bourgeois ideology, a radical movement based on students will decline or even disappear if the original motivating issue subsides. This is what has happened on Australian campuses following the end of Australian involvement in the Vietnam war. But student Maoism declined not merely because of these general reasons, but also because of its own theoretical and practical limitations. It isolated itself from the mass of students; it failed to develop a coherent orientation to the working class; and it succumbed to petty-bourgeois nationalist ideology.

THE REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-WAR MOVEMENT IN SYDNEY - RESISTANCE

The social base of this movement was similar to that of the equivalent movement in Melbourne - students and radical youth who revolted with moral outrage against the war, and against the personal effects of conscription.

The Sydney Trotskyists, divided between the Australian Revolutionary Marxists (ARM) - the Australian section of Michel Pablo's international grouping - and a loose grouping headed by Bob Gould who were sympathetic to the United Secretariat of the Fourth International, also suffered under the weight of the backwardness of Marxist theory in Australia, and of isolation from the working class. Nevertheless, the Gould group began to make its presence felt in 1967. Unlike the revolutionaries in Melbourne, this group was not constrained in the streets or still absorbed in an ALP-led body like the Vietnam Day Committee. By building upon the remains of the ALP anti-war campaign in Sydney it was able to outstrip the Peace Establishment (and the CPA), establish a radical anti-war body (the Vietnam Action Campaign) under its own control, and a broad off-campus youth organization (Resistance) with headquarters where the VAC had just opened a bookshop, the Third World. Within a very short period, a Trotskyist group had established its hegemony over almost the entire far left in Sydney. Development in this city would have to occur through further fragmentation within the Trotskyist movement. For the meantime, this was prevented by an eclecticism and softness that enabled the Resistance leaders to accommodate the political ideas of potential rivals both within and without the movement. It is worth noting that no "New Left" of socialist inspiration got off the ground in Sydney.

AN INTERLUDE - THE REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST ALLIANCE

For a moment both the dominance of Resistance and the vanguard role of the Maoists appeared to be threatened by the venture of another Sydney-based Trotskyist organization. The Australian Revolutionary Marxists sponsored the formation of a Revolutionary Socialist Alliance (RSA), whose founding conference in Sydney in January 1969, drew 120 revolutionaries - from all states, and whose influence within the left was substantial.

The RSA represented a response to the campus revolt and an attempt to universalize the central strategic demand of student power - "self-management" - for every other social layer, including the workers. The RSA hoped to be able to synthesize the demands of the various single-issue movements, and in the name of a working class orientation, bridge the chasm between the radical movements in the various states.

In 1969, however, the young revolutionary left was too immature to create a viable revolutionary socialist alliance. The objective possibility of achieving links with the workers certainly existed within the reach of the RSA. But the members themselves either did not see links with workers as a priority or were not sure of how to achieve them other than by the artificial raising of the slogan of self-management at every opportunity. Thus the RSA was not able to develop a coherent strategy for revolution in Australia. It succumbed as soon as its own limited perspective and set of demands were accommodated by another force - the Communist Party of Australia.

THE PREDICAMENT OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY OF AUSTRALIA

In late 1968, the Communist Party of Australia found itself isolated from the new force of student radicals as a whole, who, though divided over the question of revolutionary strategy, had become a revolutionary nucleus that threatened to relieve the CPA of its ostensible raison d'etre. Already France had shown how isolated from them the Communist parties were.

The new movements in the various states were linking up. Brisbane's Society for Democratic Action (SDA) had finally become a force in its own right after nestling beneath the CPA wing since its inception. It had established ties with the Monash Labor Club and the Sydney RSA. Denis Freney's propaganda for RSA directed at CPA militants had had some effect in interesting them in the concept of self-management, forcing the CPA to itself adopt a position on the question. In Melbourne, the Monash movement had established dual power with the Peace Chiefs in the anti-war movement, and the Bakery had already become the most active radical centre.

THE LEFT ACTION CONFERENCE - A STORM IN A TEACUP THAT DRENCHED THE LEFT

In Sydney, in April 1969, the Communist Party of Australia sponsored a Left Action Conference. The conference was perhaps the most decisive turning point in the development and fragmentation of the far left. At the same time it was much to do about nothing. When contrasted with the O'Shea events[4], which occurred only a month later, and upon which it had no effect, the conference pales into insignificance.

The Prague invasion had given the Communist Party leadership an opportunity to create the impression that it had broken with its past and that de-Stalinization might also lead to the party becoming revolutionary. By the time the Left Action Conference had arrived, the CPA had managed to refurbish its image.

The conference was all that the CPA desired. It was one that masqueraded as an attempt to unite the left - it had the very opposite effect. It resulted in the most serious fragmentation that had so far occurred. The CPA staved off a threat to replace it as the main radical force and reasserted its claim to be the party with whom all radicals had first to come to terms. Previously they had been prepared to unite against it; now there were conflicting attitudes.

THE AFTERMATH OF THE LEFT ACTION CONFERENCE

FURTHER FRAGMENTATION OF THE NEW REVOLUTIONARY LEFT

The fragmentation following in the aftermath of the Left Action Conference occurred along the following lines:

- By knocking its ideological feet from under it, the Left Action Conference dealt the final blow to the RSA and it disintegrated soon after. Denis Freney, its chief spokesperson, joined the CPA in April the following year.

- The conference confirmed the suspicions of the members of the Monash Labor Club about the motives of the CPA in sponsoring the conference. The seduction of their recent allies by the CPA hardened the new converts to "Marxism-Leninism" in their attitude to the rest of the left.

- In Brisbane, the Revolutionary Socialist Alliance (RSA ex-SDA) severed its ties with the now obvious "Marxist-Leninists" in Melbourne and temporarily reunited with the new-look CPA.

- The differences between the main Sydney movement (Trotskyists) and the main Melbourne one (Marxist-Leninists) were becoming clearer, and they went their separate ways.

- Back in Melbourne, WSA established itself in January 1970 upon the ruins of a once-unified Melbourne movement, now polarized into "Marxist-Leninists" and others (some of whom remained "loose Maoists"). Those unprepared to unquestioningly adopt "Marxism-Leninism" had to clarify their ideas. One section of the movement however, the "New Left", had begun to develop its ideas in opposition to the crude theories of the Maoists as far back as 1967. It counterposed the Gramscian notion of "counter-hegemony" to the Maoists' explanation for the basis of capitalist power in modern societies - the naked violence of the state apparatus. Now the CPA had driven a further wedge into this fissure. In its traditional tailist fashion, it donned the "New Left" garb itself and embraced those whose attitude had warmed to its "new-look" programme. One group associated with the "New Left" founded the journal Intervention in the early part of 1972. Another ultimately joined the CPA, forming a Left Tendency in 1973.

THE FIRST APPROXIMATION TO TROTSKYISM

The only current on the radical left in Australia which was relatively unaffected by the outcome of the Left Action Conference was the Trotskyist movement at Resistance. In 1969 it went from strength to strength, building the anti-war movement in that city by drawing in hundreds of high school students and radical youth. Eclecticism and organizational wishy-washiness allowed it to assume hegemony of the far left in Sydney, but there was a limit to how long such methods could work. By 1970 Resistance was surrounded by hostile radical forces in other cities who were beginning to adopt tighter programmes and organizations. In February, a faction fight ensued which resulted in the eclipse of the old leader Gould and a frenzied scrimmage for the Third World Bookshop.

The new leadership took the reins under a standard which represented nothing more than an attempt to establish the same youth orientation and the same political methods on a higher level, i.e. a tighter organizational footing. The fight was waged not against Gould's political guidelines, but rather his failure to implement them. The new organization, the Socialist Youth Alliance, made great play of the programme that the new leader, Percy, had witnessed at first hand in the United States and had imported into Australia on his own return. This finished programme could be so facilely adopted because, unlike revolutionary workers' organizations, sects and organizations based on the radicalization of youth do not require the development of theory and practice. They rest content with the panacea of dogma. Gould had created the youth movement - it was the task of others to build upon it.

THE QUEENSLAND LEFT

It wasn't until relatively late, in 1970, that the fragmentation which had been creating schisms in other states finally hit the new revolutionary left in Brisbane. When it did, a movement that had been the model of unity was reduced to splinters.

In contrast with other states, an original antagonism between the new radical forces and the conservative left did not exist in Queensland. A handful of New Leftists formed the Society for Democratic Action (SDA) on the Brisbane campus in August 1966, and in 1967 launched a campaign against a State Traffic Act that had prevented them from demonstrating against the Vietnam war. Not only the student body but workers too were mobilized to destroy the Act. The same year, SDA established a discotheque (FOCO) at the Trades Hall, with the co-operation of the Trades and Labour Council and the Young Socialist League (ex-Eureka Youth League), the Communist Party youth organization. So slight, at first, were the political differences between these bodies, that their joint project to contact the youth of Brisbane remained viable throughout 1968.

But by the Left Action Conference, SDA had moved to the extreme left. The French May and the invasion of Czechoslovakia had convinced it of the importance of self-management. It changed its name in April 1969 to the Revolutionary Socialist Students' Alliance (RSSA) and formed an off-campus adjunct, the Revolutionary Socialist Alliance (RSA). At the Left Action Conference, the RSA's ideas were acclaimed. The Communist Party decided to sponsor an investigation of self-management and a Socialist Humanist Action Centre (SHAC) in its Brisbane headquarters.

The Left Action Conference also overwhelmingly endorsed Brian Laver's SDA motion calling on the whole left to support the military victory of the National Liberation Front in Vietnam, and to adopt this as its policy in the anti-war movement. When Laver attempted to actually put this policy to the crowd at the first Moratorium the following year, he was muzzled and bridled for half an hour by a battery of Communist and Labor dignatories. Not long afterwards, the Socialist Humanist Action Centre was closed down. The shattering of its alliance with the Communist Party in 1970 forced the new revolutionary left in Brisbane, until then united in the RSA and the RSSA, to reconsider its whole strategy. Late that year, the first of a series of crippling splits occurred. The RSA split into the Socialist Union, which was shortlived, and the Revolutionary Socialist Party. The programmatic crisis encouraged the search for panaceas, and for the all-encompassing "total perspective" of a finished programme. The tendency developed for revolutionaries to seize upon the finished programmes of international organizations that seemed to offer a solution to the problems of the Brisbane left. Further fragmentation, and the crystallization of sects, occurred on this basis. Early in 1971, the Revolutionary Socialist Party itself split. The majority of the organization, clinging religiously to the simplicity of the slogan of self-management, had accepted the anarchist ideas of the Solidarity Group in Britain. They eventually formed the Brisbane Self-Management Group (SMG). The minority of the RSP had adopted the finished programme of the Fourth International and split as Trotskyists to form the Labor Action Group. Labor Action split in turn not long afterwards between those who remained loyal to Ernest Mandel's Fourth International, and those who were won during the course of 1971 to Gerry Healy's Fourth International. The latter, a small minority, joined the Socialist Labour League at that organization's founding conference in December 1971. The Mandelite majority became the Brisbane Branch of the Socialist Workers' League when they joined the SWL in January 1972. But unable to accept ideas originating with the SWP in the United States, they split from the SWL the following August to form the Communist League.

Sects developed more rapidly and dramatically in Queensland, but, throughout 1971 and 1972 they mushroomed in every state, becoming the general form of a new phase in the process of the fragmentation of the revolutionary left. The student and anti-war movements boiled to a peak with the Moratoriums, and then rapidly subsided. At first, the radicals who had built these mass movements found themselves isolated, atomized and suffering from the general crisis of perspective into which the left had been plunged. When they began to coalesce, they did so in sects.

THE EMERGENCE OF SECTS

THE DECLINE OF THE MASS MOVEMENTS AND THE EMERGENCE OF SECTS

The relative economic stability of the long post-war boom, which accustomed both blue and white collar workers to job security and personal consideration, has gradually undermined the "depression mentality" which in an older generation of Australians produced an attitude of slavish subservience to employers (and other authorities). At the same time, post-war capitalism required the systematic inculcation in the population of the values of a consumer society. The potential created by the relative economic prosperity for the self-cultivation of the individual was incompatible however with a mindless consumer mentality.

Thus, after a certain period of "boom" conditions, there was an increasingly strong reaction against the inhumanity of capitalism. A number of responses have developed based on a refusal to accept that society should be regulated by production requirements and that the profit motive should take priority over human considerations. The anti-war movement was the first. It popularized the idea of collective protest activity. It involved thousands of innocents and led many of them to conclude that the solution to such specific issues was an overall one - the destruction of the social system as a whole. In the anti war movement, as it passed its zenith, there appeared seekers of a total perspective and the organizational means to realize it. At this point, the crystallization of sects became the pattern of development of the revolutionary left.

There has been one important exception to the proliferation of sects in this period - the womens' movement. But in an outline history of this size it would not have been possible to do justice to a movement so diverse, complex and heterogeneous as Womens' Liberation.

The sects were not produced by ideas alone, but also by social forces. Their peculiarities are explained by the fact that they came into being as a result of differing responses to the various social forces. Some responded to the issues which came to the fore during the post-war boom while others responded to the end of this boom - the capitalist economic crisis.

THE FIRST APPROXIMATION TO TROTSKYISM CONTINUED - THE SOCIALIST YOUTH ALLIANCE

The Socialist Youth Alliance (SYA) became the first sect to coalesce amongst the discontented of the anti-war movement in Sydney when it scooped the pool with a split in Resistance in the winter of 1970. The new organization maintained the Resistance tradition however, by involving itself solely in single-issue campaigns which, because workers can become involved in them only as citizens, have by their very nature excluded the proletariat as a class. Within these various "mass movements", SYA has avoided the task of raising the participants from a sectoral consciousness (consciousness of one particular form of oppression) to a revolutionary Marxist consciousness, i.e. of transforming radicals into revolutionaries. Nor does it try to give these movements a working class orientation. SYA attempts to justify its failure to orient to the working class by claiming that the working class is not a fruitful field to recruit in. It starts, not with the needs of the class struggle but with what it shortsightedly conceives as its own ends.

But the single-issues upon which SYA and its fraternal organization, the Socialist Workers' League (SWL), have based themselves have begun to assume less importance beside economic problems and the movement of the working class in response. In a period of working class upsurge, a group that has always paid lip-service to the historic mission of the working class must make at least token efforts at involvement in workers' struggles, if only so that it may pursue in good conscience its primary commitment elsewhere. This does not mean however that SWL/SYA's work in the class is of a communist character. On the one hand, when directed at the rank and file, it is spontaneist; on the other, it attempts to apply pressure to move the trade union bureaucracy to the left.

CAPITALISM IN CRISIS AND THE SPONTANEOUS UPSURGE OF WORKING CLASS MILITANCY

In 1968-69, the United States and some European countries experienced a long recession. The ongoing crisis of the American dollar forced the United States to act. On August 15, 1971, Nixon announced a 10 per cent surcharge on imports, and the renegging on the convertability of the dollar into gold; acts which threw the parities of international currencies into the boiling pot and disrupted world trade. All countries were plunged into recession. The Lucky Country was swept into the mainstream of the world economy, giving it its highest rate of unemployment since 1961.

In Australia, inflation also began to accelerate along with the trend in other capitalist countries. In early 1971 official recognition was given to inflation and Hawke obligingly diverted working class discontent for the time being with the farce of "fair prices - fair profits" to be attained at Bourke's - ACTU store.[5]

By 1972, the working class had begun to react to the rapid erosion of its living standards. Strikes were transformed from twenty four or forty eight hour stoppages into ones extending for a number of weeks. Although working class militancy was goaded by the escalating inflation, it was hindered in the early part of 1972 by the effects of unemployment, and in the latter half by the schemes of union bureaucrats manouvering for the return of a Labor government. Nevertheless, 1972 marks the beginning of the recent surge of working class militancy.

Prior to this, those issues that dominated the attention of society, such as Vietnam, were of the kind that inspired a moral response, and the radical movement reflected this. Since then, the community has been preoccupied with economic problems, and the revolutionary groups that have emerged since are all a product of this changed social situation.

THE SOCIALIST LABOUR LEAGUE

Some of those who had been radicalized by the anti-war movement, and who were looking for a "total perspective", also attempted to come to grips with the new reality. The Socialist Labour League was the first sect to crystallize from the ranks of these. It was formed in December, 1971, with branches in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane.

In Sydney, a study group, Workers' Action, disenchanted with the single-issue youth vanguardist fixation of Resistance and others in that city, formed in late 1969 and devoted itself to coming to grips with Marxist theory. Before long, it became weary of its ambitious study programme and made a leap of faith, importing the finished programme of the Socialist Labour League in Britain.

The Melbourne branch of the SLL derived from a split in the Tocsin group - an assorted lot of individuals associated with the Victorian Labor College. The other splinter formed the embryo of the Marxist Workers' Group, later the Socialist Workers' Action Group (SWAG - see below). In Brisbane, the SLL attracted only a small minority of the Labour Action Group whose majority joined the SWL.

The Socialist Labour League held to three articles of faith: the capitalist crisis, an orientation to the working class, and the need to build a revolutionary party. When only a handful on the Australian left believed in these things, but paid no more than lip-service to them, the SLL set out to make them a reality thrusting them in the face of all the disbelievers. This marked a step forward for the Australian left, awakening others to these forgotten truths.

The Healyites themselves have fallen far short of their worthy aims, and now thrash about in the wilderness running kiddies' functions. There is a world crisis in Healyism and it may not be long, with or without a shove from Gerry Healy himself, before the Australian SLL goes the way of its mentors in Britain and the United States.

THE SOCIALIST WORKERS' ACTION GROUP

Melbourne's Socialist Workers' Action Group (SWAG) originated in 1972 as a study circle composed of former Tocsin members. A large proportion of its members since have been students, and it has concentrated on the campus. In assessing individual events and advancing relevant strategies for students, SWAG has had success.

SWAG's trade union work, mainly white collar so far, has been spontaneist and economist, however. It has perhaps failed to differentiate between students and workers. When students act, they often read, question and develop an understanding by themselves. Workers, on the other hand, rarely transcend trade union consciousness if their trade union struggles are conducted simply as trade union struggles. Currently, SWAG is moving hesitantly towards involvement in blue collar areas. If this is to be explained by the increasingly strong influence that the International Socialists in Britain has had upon the group, SWAG's blue collar work will be spontaneist and economist too.

SWAG has evolved without a codified programme, so that though it has been able to drift in its practice towards Marxism-Leninism, it has not been forced to grapple with basic Leninist concepts. For as long as it was not frozen to a definite programme, SWAG's future was open - it could develop a truly Marxist programme or attach itself to any one of an infinite variety of fads. After being repelled for so long by the imported programmes of other sects however, SWAG at this late hour has succumbed to, and imported, the programme of the International Socialists. If this process is not nipped in the bud, SWAG's ideas will have become as ossified as those of the other sects.

THE COMMUNIST LEAGUE

In the late sixties, differences began to develop within the United Secretariat of the Fourth International between the European-based majority and the minority led by the Socialist Workers Party of the United States. A central question in the dispute was that of orientation. The majority stressed the importance of an orientation to the working class whilst the SWP insisted upon a strategy based on single issue campaigns largely divorced from the working class. In most countries a tenuous unity was maintained, but not so in Australia. Those who could no longer accept the SWP's orientation as an appropriate response to the new reality of the working class upsurge split to form yet another sect, the Communist League, in August 1972. The split was led by those who had previously been members of the Brisbane group, Labour Action. It siphoned off from the SWL those concerned with developing a working class orientation, so that once again the SWL/SYA was saved from the jaws of temptation.

But all was not well with the new organization. It took the theories of the Fourth International as dogma and applied them to Australia uncritically. In particular, it took the Fourth International's analysis of the emergence of a new vanguard (i.e. a broad layer of anti-capitalist elements to the left of Stalinism and social democracy) and tried to find such a phenomenon in Australia. Since there are very few workers in Australia who fit this description, the Communist League's search for the new vanguard has tended to lead it away from the working class and towards campaign politics. It was possible for it to have a formal orientation to the working class but to continue to have a practical one to other strata. As the crisis in capitalism has deepened and the workers have pushed other groupings from the centre of the political stage, the contradiction between the Communist League's programme and its practice has become obvious, leading to demoralization. And so slender are the CL's real differences with the SWL that it has not hesitated to endorse a recent proposal of the SWL for the rapid fusion of the two organizations, a fusion which will be arranged on the basis of the politics of the larger organization (the SWL).

THE SPARTACIST LEAGUE

The Spartacist League is a fully imported model without a predecessor in the Australian left. Only when the shores of New Zealand appeared not-so-green, did it set out on its pilgrimage to the seemingly lush revolutionary fields of Australia.

Not learning the lesson of its failure in New Zealand, that its unmodified imported programme of "building the party from the top down" had become even more irrelevant with the decline of the youth mobilizations of the sixties and the anti-war movement, the Spartacist League's only impact in Australia has been to attract hostility. Its perspective is an anachronism in a period of deepening working class militancy.

Because it possesses the mentality of the sect fully blown, the Spartacist League will certainly not grow - though its fanaticism may enable it to exist indefinitely, and parasitically, on the periphery of the class struggle (unless, of course, there is another migration to still greener pastures).

WORKERS' CONTROL - THE INSTANT PANACEA

Ideas of workers' control had circulated on the Australian left after the French May of 1968. With the working class upsurge many were prompted to acknowledge at long last the need for an involvement in workers' struggles. Workers' control ideas became popularized on a broader scale. The left has always faced the difficulty of bridging the chasm between itself and the working class and of turning workers' struggles in an anti-capitalist direction; most converts to workers' control embraced it as the ready made solution.

In the meantime, militants in New South Wales put their version of workers' control into practice. At Harco Steel, and at the Sydney Opera House site, they experimented with a new tactic - the work-in. Against this background, a Workers' Control Conference was convened at Newcastle in Easter, 1973. The conference was the first large and representative gathering of the Australian left since 1971. It ponderously gnawed at the elusive trilogy of Workers' Participation, Workers' Control and Workers' Self-Management, and genuflected to the Green Ban - which had put workers' control on the tongue of the man in the street and Jack Mundey into the hearts of the populace.

The organization that had done most to publicize the prevailing interpretation of workers' control and that benefited most from the short-lived workers' control movement, was the Communist Party. However, only two months after the oratory of the Communist Party's Laurie Carmichael had becalmed the workers' control conference into an attitude of awesome respect, it was being used to cajole back to work the striking Ford workers at Broadmeadows who were to show such a healthy disrespect for bourgeois property.

Workers' control can expose the domination of one class by another. As far as the CPA and some others are concerned, workers' control revolves around the psychological aspects of alienated labour, seen as merely another form of inhumanity. In the case of the Green Bans of the CPA's then captive NSW Branch of the Builders' Labourers, workers' control became a showcase for the refined sentiment of environmentalists, rather than being based on the class interests of workers. It came as no surprise that Gallagher and his little band of thugs were so easily able to overthrow the originally fearsome NSW leadership.

THE OLD REFORMIST LEFT - METAMORPHOSIS OR LAST GASP?

THE COMMUNIST PARTY DONS ITS HUMAN FACE

Only once has the Communist Party been a force in Australian political life - during the second imperialist war, when patriotism was at a premium. In the years that followed, it became obvious to some Communists that a repetition of the golden success of the war years would follow only if the party cut the umbilical cord that tied it to Moscow.

However, it wasn't until the implications of the disintegration of the Stalinist world monolith could no longer be ignored, that the party began to adjust by seeking an independent way, an "Australian road to socialism". The first breakthrough for those Australian communists who had advocated this "polycentrism" was achieved in Victoria when, into the void left by Ted Hill's rigid and intransigent stalwarts, crept a leadership of the most pragmatic inclination, the "Italian-liners".

In the thirties, reformist social democracy embraced a new philosophy, Marxist Humanism (inspired by the works of the young Marx), to counterpose an "ethical message" to both the sordid realities of capitalist life and to the socialist revolution. With the mass communist parties becoming an integral part of European society after World War Two, Stalinism itself permanently assumed a reformist character. The Italian Communist Party in particular, began elaborating upon the ideology of Marxist Humanism to legitimize its new role, distorting the ideas of its founder, Gramsci, and twisting his notion of "hegemony" into an excuse for an "ethics revolution".

Soon the national leadership of the Australian Communist Party, under Laurie Aarons, was itself espousing the ideas first introduced into the party by the pacesetters in Victoria. And when it became clear to the party leadership that many from the New Left student intelligentsia, for whom Stalinism represented nothing more than theoretical ossification, were prepared to believe that the CPA may have begun to develop in a revolutionary direction, the drive against "conservative" Stalinist ideas within the Communist Party accelerated. Eventually, some revolutionaries of the New Left joined the party. Those who formed the Left Tendency however, were soon forced to take issue with the ideological foundations of Marxist Humanism.

THE REALITY BEHIND THE HUMAN FACE

The effect of Marxist Humanism is to blunt the razor edge of the class struggle with moral protest consisting of an appeal to the "conscience of humanity" - which is nothing more than an appeal to the ruling (class) opinion. The philosophy which is spontaneously generated (and therefore bourgeois) within workers' control, women's liberation, gay liberation, environmentalism and other movements that have emerged in recent years, is assimilable into Marxist Humanism. Therefore, once the philosophy of Marxist Humanism had become the vogue with the Communist Party leadership, the party found that it could adapt to the new movements and make inroads into them. These important human issues require a class response: from the Communist Party they got a humanistic one.

THE CLOCK STRIKES AND A CINDERELLA COMMUNIST PARTY TURNS BACK INTO A RUSSIAN PUMPKIN

The Communist Party's fortunes steadily declined throughout the post-war period. The odium which it had aroused in Australia during the Cold War by its close identification with Moscow remained as strong an obstacle in the period of detente. It was one with which a frustrated party leadership had to contend if the CPA was ever to become popular. The invasion of Czechoslovakia, which was too much for even the CPA to swallow, provided the innovators within the leadership - Aarons, Taft, Sendy - with the opportunity to broadcast their determination to be independent.

Though it had disowned the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the leadership did not embark on a fundamental reappraisal of the nature of the Soviet Union and of the material basis of Stalinism. Hence it did not (and was not able to) analyze its own avowedly Stalinist past from the point of view of Marxism. The leadership itself had been trained in the Soviet Union and the Peoples' Republic of China. It had been nurtured in the womb of the Australian party in the hey-day of its orthodoxy. Though the party began to distance itself from the Soviet Union, its break, being merely organizational, was not absolute. The leadership did not polemicize within the party against the ruling bureaucracy of the Soviet Union to challenge, or weaken, the loyalty to the USSR of the long standing members (the overwhelming majority of the membership). The CCCP tried to exploit this loyalty to outmanouvre the renegade group, and detach the membership from it. It split the Communist Party, forming a new outpost of the Kremlin (the Socialist Party of Australia), though this took with it only a minority.

TWELVE O'CLOCK

Moscow then threatened to banish the CPA from "the world communist movement" if it did not disclaim its description of the Soviet Union as "socialist-based". This was too much for many of the remaining members, who, while being prepared to support a degree of independence from the Soviet Union, were not prepared for an outright break. Into the breach, as leaders of a new right wing, stepped Taft and Sendy - polycentrists of the fifties now with an opposite orientation. They used the issue and the feeling of loyalty to the Stalinist Mecca to restructure the leadership in their own favour, but also to prevent the emerging general orientation typified by Jack Mundey from going beyond "reasonable" bounds. Aarons continued unrepentant, and a split appeared inevitable. But in mid-1974, at the party's National Congress, the faction surrounding Aarons capitulated, and the seemingly irreconcilable factions easily discovered common ground.

The future of the Communist Party is in the hands of its existing leadership. This leadership is in firm control and will not be replaced. It retains its longstanding methodology. Now, whenever it does eschew the trusted formulae of the past, it can only lapse into one form or another of populism. The Communist Party will therefore remain immune to revolutionary logic. It has failed every practical test of its much vaunted "leap from the past". In September 1973, when a savage coup burst over the Chilean revolution, the Communist Party persisted in its apology for Allendism. Today, with the fate of the Portuguese revolution still undecided, the CPA continues to defend the indefensible - the practice of the Portuguese Communist Party. It is also generous in its praise of the electoral opportunism of the Japanese and French parties, and of the "historic compromise" of the Italian Party. It welcomes the USSR's recent attempt to bind the European Communist parties together once again in what can only be an effort to forestall, for as long as possible, the impending continent-wide upheavals. This year, at the most critical moment for builders' labourers defending themselves against Gallagher, the CPA, unable to organize significant defence at the best of times, acted to defuse the awkward situation in the BLF for the sake of peaceful co-existence within the trade union bureaucracy.

Though the precise direction of the Communist Party is uncertain, one thing at least is a foregone conclusion - that in the vortex of a deepening social and economic crisis, the Communist Party will be buffeted from pillar to post. Once again transparently reformist, it will find it impossible to masquarade as a serious revolutionary force. Nor will it be able to split those to its left as it has done so successfully in the past.

THE SOCIALIST LEFT - A SHORT-LIVED REJUVENATION

For a brief period beginning late in 1970, a split of potentially far greater importance loomed - in the Labor Party.

To win acceptability amongst the burgeoning suburban middle class and satisfy the media barons, Gough Whitlam had long led a campaign within the Labor Party to have appointed a leadership more amenable to his extreme opportunist style - in particular to break the influence of left wing unions upon the Victorian Central Executive of the party, the last remaining embarrassingly left wing stronghold in the ALP. Whitlam became parliamentary leader in 1967. He de-emphasized Vietnam, restructured the Federal Executive to include parliamentary leaders, and then, preparing for the kill, finally stage-managed a confrontation with the VCE over State Aid which culminated in his intervention into the Victorian Branch, to purge the executive, in November, 1970.

The Victorian Branch had been the one most affected by the 1955 ALP split. Leaders of the Trade Union Defence Committee had gained firm control of the State Executive, but, though including a number of self-confessed revolutionaries, they did little in the next fifteen years to involve the rank and file of the Branch. Against Whitlam's far greater bureaucratic resources, their customary wheeling and dealing was found wanting, and no-one was more surprized than they when a left wing protest newsletter, Inside Labor, began to circulate amongst the rank and file and meet with a response. Caught up in a groundswell of protest against the intervention they were forced to participate in the formation of a left wing faction - the Socialist Left - defending traditional ALP socialist policies. But under the dead weight of this traditional ideology, and unable to envisage a life outside of their political home, they avoided an expulsion or a split at all costs and thus were able to produce only a piecemeal programme. The widespread rank and file support which had thrust them forward was soon frittered away.

When the then existing Trotskyist fragments flooded into the Socialist Left in 1971 to recruit, the Socialist Left leaders, theoretically at sea and politically embarrassed by the proffered programmes of the Trotskyists, began to promote the bureaucratization of their organization. Before long the Socialist Left had become a sclerotic caricature of its former self. For the 1972 elections, its leaders closed ranks behind Whitlam, and after, bound themselves even more securely to him, sullenly acknowledging his "good" deeds and keeping quiet on the others. Soon however, as if it wasn't frustrating enough to win by a whisker in the cliff-hanger 1974 election and remain bedevilled by a hostile senate, the government found itself at the mercy of a world economic recession. Then, fulfilling Gough Whitlam's long ambition and marking the final consolidation of his hold over the party machine, Labor at last wrote into its constitution a commitment to private enterprize at its Terrigal Conference in January 1975. Almost immediately afterwards, Whitlam promoted his co-thinkers to the powerful positions in the ministry, displacing such Labor stalwarts as Cairns and Cameron. Thus, in quick succession, he was able to achieve what would have been unthinkable when the government had first been elected, and gain absolute control of the parliamentary party. When Whitlam has been most vulnerable however, and through each crisis - Terrigal, the ministry reshuffle, and the "loans affair" - the Socialist Left bureaucrats have stood helplessly on the sidelines, immobilized in manoeuvre and machination. Their reaction to the 1975 Budget of the Whitlam government was no different.

Many revolutionaries joined the ALP because there was nowhere else to go. Seeing the Communist Party as irrelevant, they believed that there was at least something to be gained by promoting their own politics within a party based on the trade unions and with an electoral base in the working class. As a result of Whitlam's campaign to remodel the party however, the ALP has been transformed from a federation of relatively autonomous State Branches into a centralized national party, its policy being formulated by specialist committees and being determined at the level of Federal Executive and Federal Conference. The day when a rank and filer could conceivably influence policy has long passed. Even if Whitlam was to be banished following a Federal election defeat, the centralization of power would simply be transferred to new hands, probably Hawke's. Though such a party crisis might result in the scattering of authority to some extent, the centralization would remain intact. This situation makes working inside the ALP untenable for individual revolutionaries.

CONCLUSION

The panorama of the Australian left reveals a grim situation. The mummified Communist Party is bad enough, but for an alternative we are expected to choose from among a multiplicity of impotent sects. And yet the need for a genuine mass-based revolutionary party in Australia has never been more urgent.

The fragmentation which produced the sects took the revolutionary left as a whole another step forward, invoking revolutionary needs of the most demanding order - the need for an implantation in the proletariat, the need for an understanding of the crisis afflicting world capitalism, and the need for a genuine mass-based revolutionary party.

The sects of themselves, with their limited theoretical and practical capacity, have been unable to satisfy these needs. The revolutionary left is again at an impasse. If it is to continue to go forward, it will have to change its very nature. Revolutionaries will have to dispose of the outmoded form of sects in which they have been working and prepare for a further qualitative leap - revolutionary regroupment. To regroupment, the attitude of the sects themselves is inimical. It will have to proceed in spite of them.

the principles of a revolutionary regroupment

The importance of the building of a revolutionary communist party is a constant concern of revolutionaries. Nevertheless, there are periods, such as the present in Australia, when the urgency is especially sharp, the situation on the left particularly critical, and the opportunities for building a revolutionary party unusually favourable. To face up to the demands that the class struggle places on revolutionary socialists in this country, we call for a revolutionary regroupment of the Australian left.

WHY REGROUPMENT?

Many people sympathetic to revolutionary politics remain altogether outside the organized tendencies. Among the divided, squabbling groups to the left of the Communist Party of Australia, and the Australian Labor Party, they see no clear alternative. A serious and sincere effort for revolutionary unity on a principled basis could draw many comrades, who will otherwise be lost to the movement, into revolutionary work. These potential members of a revolutionary party are so confused, or repulsed, by the doctrinal wars of the sects, and disappointed with the irrelevance of these minuscule organizations, that they will justifiably join none of them. The sects have therefore been unable to revolutionize the thousands that are being radicalized by the social and economic crises and the flux of ideas which these crises have produced. Regroupment, on the other hand, would provide the possibility of fruitful theoretical discussion and clarification alongside practical collaboration. It could have a significant practical effect on the balance of forces.

THE PECULIARITY OF THE AUSTRALIAN LEFT

Those peculiar features of the Australian revolutionary left which distinguish it from the left of most other advanced capitalist countries - its impoverished theoretical condition, its recent origin, and its derivative nature - do not represent an insuperable obstacle to a revolutionary regroupment. In fact, for these very reasons, regroupment may be easier here than elsewhere.

In Europe, and in the United States, where the finished programmes of the sects have originated, the revolutionary organizations will not readily discard, or question, the programmes which they themselves have taken so long to evolve. The renowned international leaders have great personal and organizational influence in their own countries. They are skilled and experienced, and their authority and prestige is enormous - recruits to their own national organizations will be directly influenced by them. These organizations are larger and better organized than their derivative organizations in Australia, and hence have greater sway over their members.

In Australia, the renowned international leaders will not be present. The regroupment debate, because it will be conducted by fallible mortals, will at least be open to question. Because the programme of the derivative sects here is imported, and second hand, it may so much more easily become the object of critical scrutiny. Also, the sects in Australia are very young and small. The leadership of an Australian sect will find it more difficult to convince revolutionaries, both members and non-members, that their own particular group holds in its hands the fate of the Australian revolution. In Australia, the overwhelming necessity of regroupment should be more obvious.

The development in Australia of an abundance of derivative Trotskyist and Maoist sects has prevented the development of one or two much larger organizations. At the same time, as a result of a justified unpreparedness to accept these derivative sects at their face value, a number of independent groups, wary of the dangers of importing a finished programme, have been established. Although these groups may be spontaneist, economist or theoreticist, they too are a process, and after several years of existence have begun to question themselves.

INTERNATIONALISM - THE REALITY AND THE FETISH

The struggle in Australia is not more important than, nor can it be separated from, the struggle elsewhere. Therefore a revolutionary proletarian organization cannot be built in Australia in isolation from the fight to build a revolutionary proletarian international.

International organizations and tendencies certainly exist. None, however, is adequate or authoritative enough to qualify as the Proletarian International. None can claim that its international programme is the programme of the Proletarian International; each expresses at most only a portion of the truth. The Proletarian International must be built, both on an international and a national level. This is not to deny however, that some, at least, of the existing international organizations and tendencies will make an important contribution to building the international.

There are two conflicting theories of how to build the international at the national level in Australia. The theory supported by each "international" is that its own offshoot will, by linear growth and on the basis of its "correct line", triumph over every other claimant. As none of the "internationals", in their countries of origin or elsewhere, have been able to achieve this, it is unlikely to occur here.

The alternative view of internationalism, which each of the sects would denounce as "Australian Particularist", is that only a revolutionary party rooted in the Australian working class could claim to be a legitimate part of the future Proletarian International. Revolutionaries in Australia have small resources and are not able to create the revolutionary international by themselves. It is in building a serious internationalist cadre in Australia, and by overcoming the acute fragmentation of the revolutionary left, that they can make a practical contribution to its formation.

The internationalism of the derivative sects is abstract: each takes the truism of proletarian internationalism as its starting point but can do nothing more than mouth the ideas of its "international".

The idea that the proletarian international party can be built otherwise than on the basis of real national sections rooted in the working class is a mystification of proletarian internationalism. He or she is no internationalist who proclaims an abstract internationalism while shirking or botching the duties of an internationalist in the immediate arena - the class struggle in Australia - and amongst the immediately accessible battalions of the international proletariat.

POLITICAL GUIDELINES FOR A PRINCIPLED REGROUPMENT

It took a decade to fragment the revolutionary left in Australia. To suggest that any one blueprint or "correct" programmatic statement could overcome this fragmentation, would be absurd. Only a principled debate can.

The debate that we have in mind is one that puts the needs of regroupment before sectional interests. It would establish a framework in which positive steps could be taken to overcome mutual isolation and proceed towards programmatic agreement. Programmatic agreement is not reached mechanically - by the exhibition of finished programmes. There are certain stages through which it must pass, and certain preconditions: theoretical clarification and practical collaboration conducted in an atmosphere of mutual respect; emphasis on reaching agreement on the principles of revolutionary socialism before considering specific programmatic points.

The following series of such guidelines is our own suggestion for the principles of a revolutionary regroupment. It is not proposed in a spirit of "the lowest common denominator" and therefore does not blur the fundamental distinction between revolutionary socialism and other political trends. Nor is it so narrow as to exclude at the outset everyone but ourselves. There are a host of theoretical and practical questions that have not been covered, but we would prefer to contribute our own ideas on these more specific questions only after a framework for theoretical clarification and practical co-operation has been established. It would be foolhardy to refuse to unite until agreement is reached on every dotted "i" and crossed "t".

- A commitment to the basic guiding ideas of Marxism: the historic necessity of the dictatorship of the proletariat; the impossibility of socialism in one country; the need for proletarian internationalism.

- An active involvement with the struggles of the working class, recognising that the emancipation of the working class must be the act of the workers themselves. An orientation to the rank and file recognising the fundamental role of the labour bureaucracy as "labour lieutenants of the capitalist class". A fight for workers' democracy in the trade unions, and for the complete independence of the unions from the capitalist state. A recognition of the need for a communist leadership in the unions, achieved only through open, harsh struggle against the reformist, Stalinist, and neo-Stalinist leaders, exposing them when they prove unable or unwilling to act upon viable, alternative communist strategies for action.

- For the working class to become an effective fighting force both in the economic class struggle within capitalism, and in the broader class struggle to overthrow it, workers must organise themselves into their own class organs. Strike committees and shop committees representative of the rank and file are a more effective means of waging the economic struggle. They are a direct response to exploitation at the point of production, and therefore tend to be a more volatile form of organization. In taking up every issue as it arises they develop an authority among their constituents allowing them to express in the factories, not only the wider economic needs of the class, but its political needs also. To develop workers' power further, shop committees should be unified on a locality basis (soviets) and workers' self-defence corps (militias) organized for the practical defence of occupations and picket lines, economic and political demonstrations, etc. By their very nature, these rank and file organs can, in periods of deep social crisis, transform themselves into organs of dual power.

- A commitment to the building of a Leninist working

class combat party, struggling ideologically, politically and

culturally for communist consciousness.

To turn towards the working class is the essential, elementary wisdom of proletarian revolutionaries. The day to day working class struggle, even in a crude syndicalist form, is the raw material of communism. BUT the recurring economic and political struggles of the working class cannot of themselves, spontaneously, produce a revolutionary class consciousness. The task of Communists is to build an organization possessing this consciousness, capable of disseminating it, and capable of integrating itself into the proletariat, and of learning from it, whatever its level of struggle.

Narrow trade unionism and workerism - the tendency seeking to confine the attention of the working class to its own immediate economic struggles and the political struggles arising directly from them - must be combatted. The revolutionary socialist struggle is an all-sided one in which each partial struggle is related to the overall perspective. In any period less than one of giant revolutionary upsurge, the organic struggles of the working class remain trapped within the limits imposed upon an "interest group" bargaining within the capitalist system. In the revolutionary upsurge itself, as the proletariat demands serious political answers, a party which has previously based itself on passive accommodation to existing trade unionist struggles will be left floundering.

- United Front activity, anti-fascist committees and solidarity committees, etc., should be initiated and supported. Revolutionary organizations can be of value to the working class only by seeking to develop the widest possible activity, with the most precise, practical policies - not by proclaiming their own organization to be "the alternative" and crying "join us".

- The Australian Labor Party, in the opinion of quite

a large section of the Australian working class, is a party that

represents the interests of workers. These workers can be said to

possess a degree of class consciousness. However, if they identify with

the Labor Party, it is not because they think it is socialist. The vast

majority of Australian workers are, at this stage, unable to see beyond