SoftDawn |

China & Tibet, 2006 |

Xianyang |

Dunhuang |

Train To Lhasa |

Lhasa |

Contact Us

Dunhuang was established as part of the Han Dynasty's military policy of defeating the marauding nomadic Xiongnu tribes and driving them beyond Chinese contact. In pursuing this strategy, overland routes to the west were discovered and explored and contact was made with peoples in the "Western Regions". Trade between Chinese and people to the west got underway. As a result the Silk Road came into being and by 80 BC was in full swing.

Today Dunhuang is a medium sized regional centre with tourism being an important industry due to the nearby Mogao Grottoes (Caves).

Links are provided to maps and a historical background about

Dunhuang.

The Mogao Grottoes, or Caves, at Dunhuang are an amazing assemblage of separate hand excavated and decorated caves which were constructed over a millennium beginning in 366 AD. According to records, over 1000 grottoes were built over this period and 492 survive today in good condition.

The inspiration for the grottoes was the worship of Buddhism which first began to have an influence in China in the early centuries after the birth of Christ.

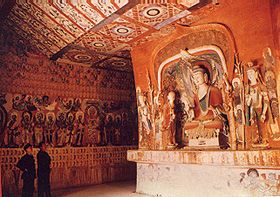

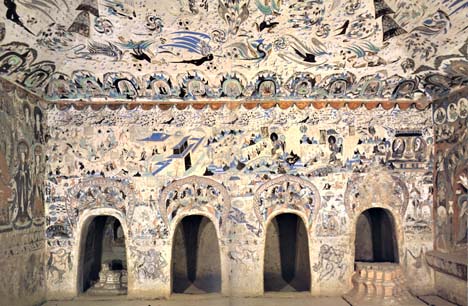

Interior of a grotto at Dunhuang. Its size can be seen by reference to the two human

observers.

Interior of a grotto at Dunhuang. Its size can be seen by reference to the two human

observers.

The size, style and themes of the many grottoes at Mogao is highly varied.

The grottoes were dug into a 1600 m long cliff face 25 km south east of Dunhuang.

Individual grottoes were excavated in the shape of a room with the plan for the grotto

determining its shape. The resulting cavity became the medium for the decoration of the

grotto. Walls were sealed and painted, niches were hollowed out and platforms were carved in

situ. Sculptured objects were brought into the grotto and installed in place. Murals were

painted and the decoration of the grotto was finished in brilliant colours and designs.

After the sea-route to India, Egypt and Europe was developed, the hazardous Silk Road went

into decline. The grottoes were abandoned and forgotten in the fourteenth century until

re-discovered in at the beginning of the twentieth century by western adventurers and looters.

Fortunately the dry desert climatic conditions has preserved many grottoes and their stunning

artwork for modern generations.

The grottoes came into prominence again when news reached Europe of the discovery of a "library cave" at the Mogao site which contained thousands of Buddhist documents going back to early times. In 1907 Aurel Stein, an archaeologist and explorer, visited Dunhuang to view the Grottoes, but heard from a local of the discovery six years earlier of the library cave by a Buddhist monk. Stein set out to win the confidence of this monk who had become the cave's self-appointed custodian. He eventually succeeded and making a substantial donation to the monk's reconstruction project was allowed to make off with 24 cases, heavy with manuscripts, and 5 more filled with carefully packed paintings, embroideries and other art relics. These he deposited in the British Museum. When his exploits were published Stein was quickly followed by others from France, Germany, Russia and Japan who carried off more treasures which "were bound otherwise bound to get lost sooner or later through local indifference". Not only did they plunder the library cave, they also chiselled off murals from the walls of grottoes and took away statues and other objects. Nevertheless, Stein's and the others' sacking of the Mogao Grottoes was met with outrage by many educated Europeans as with the Elgin Marbles controversy.

The Sleeping Buddha.

The Sleeping Buddha.

Detail of head portion of the Buddha's Parinirvana.

Cave 158 (mid-Tang Dynasty).

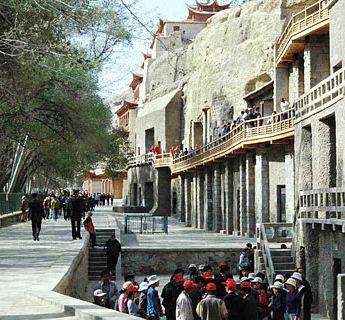

Entrance into the grottoes is via the wall and walkways build against the cliff face in the

1960s to preserve the caves.

Wall and walkways built against the cliff face in the 1960s to protect the grottoes.

Wall and walkways built against the cliff face in the 1960s to protect the grottoes.

Doors lead from a walkway into a grotto.

Photo by: Neville Agnew,

Getty Conservation Institute

Only a limited number of the caves are open to the public at any time and are opened in rotation. Visitors to Mogao are put into tour groups which are taken by a guide through a number of the available caves (different groups go to different caves). The guide explains general features and issues. Lighting is by the guide's hand-held flashlight, so it's worthwhile to take your own torch so you can look at what is of interest to you.

Excavated cliff face north of the main grotto complex with dug-out rooms for monks and

artisans.

Excavated cliff face north of the main grotto complex with dug-out rooms for monks and

artisans.

Is this how the grottoes looked before the 1960s protective wall was built against the

cliff face?

Dunhuang evolved as a busy military command post and a trading and staging centre on the

Silk Road. Buddhism developed in India and as its influence spread into China in the early

centuries after the birth of Christ, pilgrims travelled the only route from China through

Dunhuang and the Gansu Corridor to Afghanistan and then over the Karakoram passes into

Pakistan and onto India.

There is a local belief that in 366 AD a monk named Le Zun saw a vision of 1000 golden

Buddhas over the mountain opposite the cliff of Mt Mingsha, so he set to dig a cave in the

sandstone cliff and fill it with Buddhist images. Apparently, this was the impetus which

inspired a millenium of grotto construction. The wealth of Dunhuang's merchants and military

commanders was sufficient to fund this activity while the Silk Road was going strong.

Private chapels. Patrons.

There is a nine story building in front of a major grotto which can be seen in the distance

behind the trees.

There is a nine story building in front of a major grotto which can be seen in the distance

behind the trees.

After the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 priority was given to protecting

and preserving the grottoes and their contents.

Today the Chinese authorities have in place measures to protect and preserve the grottoes and

make them available for viewing by Chinese and overseas visitors.

Looting was stopped. The trees in front of the grottoes was planted to inhibit sand egress. The

wall and walkways against the cliff face were built. Restoration programs have been put in

place. Management methods have been implemented to minimise the effects of groups of tourists

in otherwise low-humidity spaces. Research programs are being conducted.

Bridge across Yanquan River leading into the Mogao Grottoes complex with the original cliff

face in the distance.

Bridge across Yanquan River leading into the Mogao Grottoes complex with the original cliff

face in the distance.

Link to site about Mogao cave art: www.textile-art.com/dun1.html

Further reading: Foreign Devils on the Silk Road. The search for the lost treasures of Central Asia. Peter Hopkirk, Oxford University Press.

Burial stupas of prominent monks at Mogao.

Burial stupas of prominent monks at Mogao.

Links are provided to maps and a historical background about Dunhuang.

SoftDawn |

China & Tibet, 2006 |

Dunhuang |

Mogao Grottoes |

Great Wall |

Dunes